Research

We use species’ evolutionary history to better understand and predict their present-day ecology. Our lab develops new statistical and computational tools to answer fundamental questions about the origins and future of biodiversity. We have four core research pillars (evolutionary ecology, ecosystem function, conservation, and human health), which are supported by two underlying supporting themes (our Ecological Fractal Network and machine learning). We work with a number of conservation programs, such as the EDGE of Existence Program, to help safeguard natural ecosystems and the valuable services they provide for humanity.

We use species’ evolutionary history to better understand and predict their present-day ecology. Our lab develops new statistical and computational tools to answer fundamental questions about the origins and future of biodiversity. We have four core research pillars (evolutionary ecology, ecosystem function, conservation, and human health), which are supported by two underlying supporting themes (our Ecological Fractal Network and machine learning). We work with a number of conservation programs, such as the EDGE of Existence Program, to help safeguard natural ecosystems and the valuable services they provide for humanity.

Theme 1: Evolutionary ecology: understanding the past and forecasting the future of biodiversity

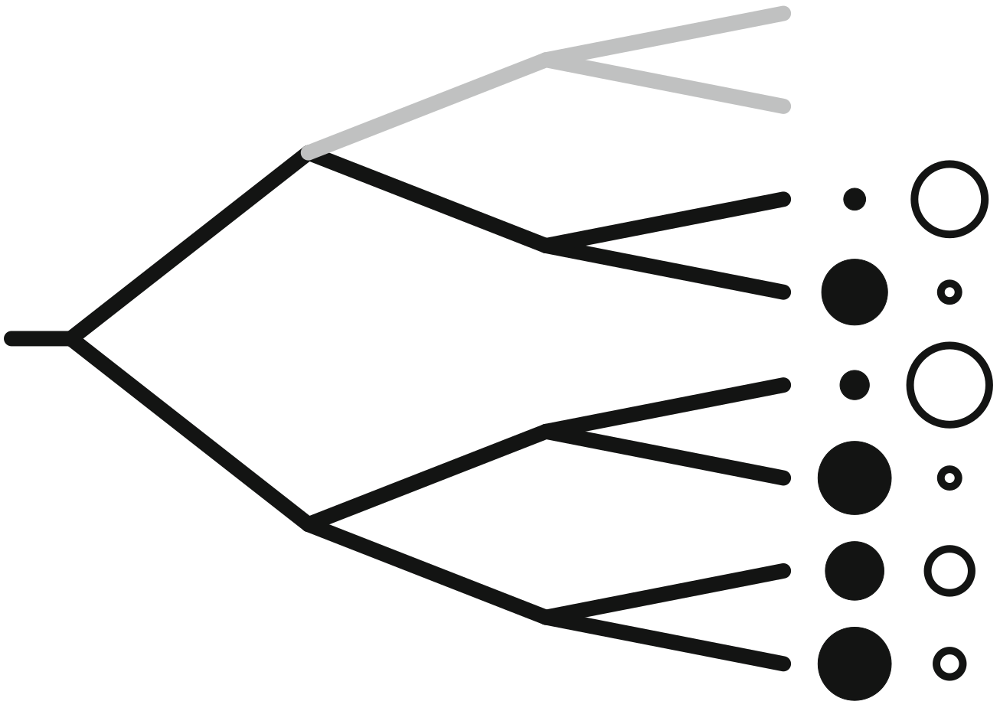

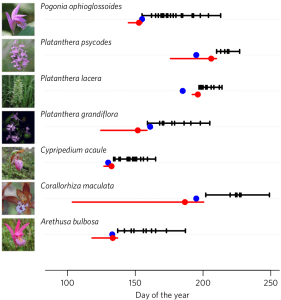

We feel that the best way to understand how biodiversity is responding to present-day threats is to understand how it evolved in the first place. The exciting challenge, for us, is to find ways to fit statistical and mechanistic models that incorporate ecological and evolutionary dynamics. To do this, we have developed and extended the Phylogenetic Generalised Linear Mixed Modelling framework, and focused on ideal study systems like our Ecological Fractal Network and long-term phenological datasets.

Relevant papers: Eco-evolutionary modelling framework | 100 years of climate-change responses

Theme 2: Evolutionary ecology: understanding the past and forecasting

Theme 2: On-the-ground conservation work

Generating meaningful products for policy-makers requires not just innovative research ideas, but also serious engagement with stakeholders to determine their needs. Our lab co-led the Zoological Society of London’s EDGE of Existence program ‘EDGE 2.0’

update. The EDGE program operates worldwide, and has trained >75 fellows working on >70 species in >40 countries. We have also worked with government agencies, such as the USDA Forest Service, to help prioritize restoration and conservation efforts. Now, in part through our collaborations with the National Trust and Knepp Estate, we are developing biodiversity measurement

Relevant papers: EDGE review | PIBO project

Potential student projects: Pick a country or taxonomic group, and apply some of our conservation algorithms to that group. Now look to see if the results match the expectations and needs of policy makers, and adjust appropriately!

Theme 3: Natural history specimens, phenology, and morphology

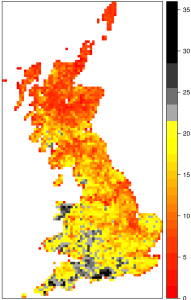

We are part of the Symbiota2 team, developing the next generation of software that powers the data stored in >750 natural history collections across the world. We are working to use that data to not just understand where species are found, but also the timing of their life-history events (their phenology) and their shape. We are beginning to use new statistical methods to examine the timing of events like migration and flower opening from museum specimens. Further, we are using the stalkess pipeline to examine changes in butterfly and plant morpology through time and across space.

Relevant papers: phenology & variance | stalkless & morpology

Potential student projects: Are flowering times in [your favourite species] keeping track with changing climate? Where are they (not), and why?

Theme 4: Making A Database for ecology - MAD

The last decade has seen a shift in how science views data: funders now require that data are released to facilitate synthetic

analyses. Yet even with open data, it is difficult to make a database large enough to answer synthetic questions because data are often deposited in different repositories and formats. Further, researchers are reticent to release older data due to a perception that they will lose credit once their data are synthesised. Working with the Bio Nerd Herd here at USU, we are developing a software ecosystem that unites discipline-specific networks via a common data language to Make A Database (MAD) to permit synthetic and multidisciplinary analyses. MAD is a living software package that makes databases from existing online sources and fully credits data collectors. MAD represents a shift in data sharing: it is a distributed, on-demand software ecosystem, not a static data release that is unsustainable long-term. MAD currently loads >20 million pieces of data for users’ immediate use.

Relevant papers: MADcomm website | MADtraits website

Potential student projects: Pick a taxonomic group, or kind of data, that isn’t currently in MAD. Fix that gap! Or use the data already in MAD to answer a new question.

To address this challenge, we develop software (e.g., the R package pez and the program phyloGenerator) to make it easier to fit joint models of the evolution of species’ traits and their ecological interactions.